Most Viewed Articles

- Real Life Cam 24 7

- Rock Band 3 Pc Game

- Asp Net C# Projects With Source Code

- Case Studies Operations Management Free Download

- Gratis Buku Fiqih Wanita

- How To Install Sygic Cracked Version Minecraft

- Descargar Software Para Control De Inventarios

- Funny Ancient Egyptian Jokes

- Disciples Iii Patch Fr

- Claro Router Keygen

- Wow Hits 2014 Download Rar

- Wsc Real Pc

- Sims 3 Baby Changing Table

- Download Office Xp Full

- Simulazione Modello Unico Persone

3D Home Software

var q 3dhomesoftwareD Design, Engineering Entertainment Softwarecontentdatamanagementglobalenproduct catalogproductsautodesk fusion 3. Optitex develops 3D virtual prototyping and 2D CADCAM pattern and fashion design software that is innovative and easytouse. Illusion. Mage Easy 3. D Animation Software Program. Dear 3. D Animator,Have you always wanted to create your own animations or 3. D Games What if I told you that you can produce animations and models like Pixar or Walt Disney easily and quickly from the comfort of your home. European studios are using. The good news is theres a sea of change that is sweeping across the animation industry, transforming thousands of lives and home studios and it lies. BEAUTIFUL Animations With Minimum Effort. Creating stunning 3. D animations is a breeze if youve got a multi million dollar budget, loads of staff and state of the art studio. Heck, why not throw in a few years studying animation at college for good measure. Up until now, thats exactly what you needed. But no longer. Because now theres Illusion. Mage, an industry leading 3. D modelling animation suite for creating cutting edge 3. D animations just like Pixar and Dreamworks in your hown home in 2 hours or less Introducing. Illusion. Mage The Complete 3. D Creation Software Suite Video Training Package Easily The Most Powerful 3. D Creation Software On The PlanetWhat youre getting is an advanced animation software and a full featured integrated modelling, rendering, animation and real time open source 3. D creation package. This hi end software suite allows you to. Create high quality 3. D graphics Produce your own cartoon animated film Draw and animate 3. D models Design your own 3. D game easily Create real time interactive 3. D content Creating and render exceptionally rich realistic natural environments. Let your imagination come alive with the easiest way to create stunning animationsGet The. SAME Software That Leading Animation Studios Are Using Over the last decade, this has evolved as an in house tool for leading European animation studios. This is your chance to get your hands on a professional hi end 3. Download freely Sweet Home 3D for Windows, Mac OS X and Linux. Products. AutoDesSys has created the standard for 3D modeling software since 1991. Regardless of your application, formZ creates accurate, photo realistic 3D. Live Home 3D is home design software for floor plan creation and 3D visualization that suits both amateurs and professional designers. D creation programwithout paying an arm and a leg. With illusion. Mage suite blender video tutorials, you can weave your own web of magic. Home of the Blender project Free and Open 3D Creation Software. Announcing The Revolutionary 3D Software That Has Helped 6,100 People In 67 Countries Create Stunning 3D Animations From The Comfort Of Their Own Home. A freeware realtime 3D modeling and animation tool that incorporates a draganddrop approach to 3D modeling. Features Imports many popular 3Dfile formats.  You DO NOT need to attend expensive courses or have any experience to use this. You will be able to produce hollywood 3. D computer animations and models like movie studios quicker and easier than youve ever dreamed of. This will set a benchmark for 3. D animation programs in the market. The ease of use coupled with a feature rich interface makes it a dream come true for animators. Richard Haney. Elmont, NYNo Technical Skills Required, Just Add Imagination. Create broadcast quality 3. D content, with the simple Point Click interface. Create your own cartoon series, 3. D games, websites and product demos. Animate astoundingly real 3. D models with east. No Technical skills required, just add imagination. The word processor revolutionized the publishing industry and now Illusion. Mage is revolutionizing the animation world, its time to enter the third dimension. Go on, see the full range of features below If You Think Maya or 3. D Max is Good, You Aint Seen Nothing Yet Let me lay it out for you this is a complete solution for high end 3. D production at an unprecedented price. It has a robust feature set similar in scope and depth to other high end 3. D software such as Softimage. XSI, Cinema 4. D, 3. Ds Max and Maya. Get the best of both worlds in 1 software It combines the architectural power of 3. D Studios Max and Animation Effects of Maya. These features include advanced simulation tools such as rigid body dynamics, fluid dynamics, and softbody dynamics, stop motion animation, modifier based modeling tools, powerful character animation tools. Even better, you can also create dynamic 3. D models by RTS animation so models can move back and forth, float, or rotate. It also offers professional CG artists a complete toolset for creating exceptionally rich and realistic environments. Thanks for offering this Seth. This is a 5 star product The results of a well lit render at the best resolution settings is truly stunning, verging on the photorealistic. Ken Foreman. Houston, TX Learn EXACTLY How To Create Your. First Animated Model With Software Video Training Illusion. Mage Blender contains the software, a complete 2. Discover How To Create Animated Cartoons Like Toy Story and Madagascar Within Minutes. Yes. Thats right. You can create your own cartoon series right at your computer with illusion. Mage. Produce cartoon animations such as Toy Story, Madagascar, Shrek from home with step by step tutorials. But more importantly, you too can create professional looking 3. D objects, add animation, and use a wide range of 3. D effects like professional studios without paying for expensive software. It is an all in one 3. D creation program suite that is suitable for both beginners and experts. In fact, you will be able to create your first animation model within 5. It can be used for modeling, UV unwrapping, texturing, rigging, skinning, animating, rendering, particle and other simulating, non linear editing, compositing, and creating interactive 3. D applications. As I have already said, this suite is just as advanced as 3. D Max Maya, however the best way to demonstrate its abilities is through some pictures and videos of real editing work. Take a look at the features and videos below Hold on to your seat and keep reading because heres an in depth look of 9 amazing features. Feature 1 Ease Of Interface. Feature 2 Advanced 3. D Modelling. Click Here to watch an amazing demo of cartoon character modelling in action Ultra realism 3. D models is possible with a full range of object types and functions. Complete versatility to create any face shape, face type or face emotion you desire. Supports a full range of 3. D object types such as polygon meshes, NURBS surfaces, bezier and B spline curves, metaballs, vector fonts. You can also perform functions like extrude, bevel, cut, spin, screw, warp, subdivide, noise. Edit the texture, sharpness, shape of any model easily and quickly. Deform any face in any way you like with tools like Lattice, Curve, Armature. Creating realistic face shapes and models is a breeze with Illusion. Mage. Feature 3 3. D Cartoon Animation. Feature 4 Realtime 3. DGame Creation Overview of Features lick Here to see a car simulation game created and rendered with Illusion. Mage. Graphical interface to edit your game landscapes and action without any programming skills Get the same software that Play. Station uses Bullet Physics Llibrary. Bullet Detection and Rigid Body Dynamics Library for realistic motion and physics You can create all types of shapes including Convex polyhedron, box, sphere, cone, cylinder, capsule and static triangle mesh. Auto collision detector and enhanced physics engine makes it easy to program your own crashes and action sequences You get full support for vehicle dynamics and that includes all spring reactions, stiffness, damping, tyre friction etc. Create realistic lighting with Open. GLTM lighting modes that includes transparencies, Animated and reflection mapped textures. Instantly playback of games interactive 3. D content so you have an instant preview of how your game looks like Feature 5 3. D Editing Compositing. Feature 6 Enhanced 3. D Rendering. Feature 7 Complex 3. D Shading. Click Here to watch actual footage of 3. D Shading in action D Shading allows you to create 3. D shapes realistically to create objects, buildings and other life like items.

You DO NOT need to attend expensive courses or have any experience to use this. You will be able to produce hollywood 3. D computer animations and models like movie studios quicker and easier than youve ever dreamed of. This will set a benchmark for 3. D animation programs in the market. The ease of use coupled with a feature rich interface makes it a dream come true for animators. Richard Haney. Elmont, NYNo Technical Skills Required, Just Add Imagination. Create broadcast quality 3. D content, with the simple Point Click interface. Create your own cartoon series, 3. D games, websites and product demos. Animate astoundingly real 3. D models with east. No Technical skills required, just add imagination. The word processor revolutionized the publishing industry and now Illusion. Mage is revolutionizing the animation world, its time to enter the third dimension. Go on, see the full range of features below If You Think Maya or 3. D Max is Good, You Aint Seen Nothing Yet Let me lay it out for you this is a complete solution for high end 3. D production at an unprecedented price. It has a robust feature set similar in scope and depth to other high end 3. D software such as Softimage. XSI, Cinema 4. D, 3. Ds Max and Maya. Get the best of both worlds in 1 software It combines the architectural power of 3. D Studios Max and Animation Effects of Maya. These features include advanced simulation tools such as rigid body dynamics, fluid dynamics, and softbody dynamics, stop motion animation, modifier based modeling tools, powerful character animation tools. Even better, you can also create dynamic 3. D models by RTS animation so models can move back and forth, float, or rotate. It also offers professional CG artists a complete toolset for creating exceptionally rich and realistic environments. Thanks for offering this Seth. This is a 5 star product The results of a well lit render at the best resolution settings is truly stunning, verging on the photorealistic. Ken Foreman. Houston, TX Learn EXACTLY How To Create Your. First Animated Model With Software Video Training Illusion. Mage Blender contains the software, a complete 2. Discover How To Create Animated Cartoons Like Toy Story and Madagascar Within Minutes. Yes. Thats right. You can create your own cartoon series right at your computer with illusion. Mage. Produce cartoon animations such as Toy Story, Madagascar, Shrek from home with step by step tutorials. But more importantly, you too can create professional looking 3. D objects, add animation, and use a wide range of 3. D effects like professional studios without paying for expensive software. It is an all in one 3. D creation program suite that is suitable for both beginners and experts. In fact, you will be able to create your first animation model within 5. It can be used for modeling, UV unwrapping, texturing, rigging, skinning, animating, rendering, particle and other simulating, non linear editing, compositing, and creating interactive 3. D applications. As I have already said, this suite is just as advanced as 3. D Max Maya, however the best way to demonstrate its abilities is through some pictures and videos of real editing work. Take a look at the features and videos below Hold on to your seat and keep reading because heres an in depth look of 9 amazing features. Feature 1 Ease Of Interface. Feature 2 Advanced 3. D Modelling. Click Here to watch an amazing demo of cartoon character modelling in action Ultra realism 3. D models is possible with a full range of object types and functions. Complete versatility to create any face shape, face type or face emotion you desire. Supports a full range of 3. D object types such as polygon meshes, NURBS surfaces, bezier and B spline curves, metaballs, vector fonts. You can also perform functions like extrude, bevel, cut, spin, screw, warp, subdivide, noise. Edit the texture, sharpness, shape of any model easily and quickly. Deform any face in any way you like with tools like Lattice, Curve, Armature. Creating realistic face shapes and models is a breeze with Illusion. Mage. Feature 3 3. D Cartoon Animation. Feature 4 Realtime 3. DGame Creation Overview of Features lick Here to see a car simulation game created and rendered with Illusion. Mage. Graphical interface to edit your game landscapes and action without any programming skills Get the same software that Play. Station uses Bullet Physics Llibrary. Bullet Detection and Rigid Body Dynamics Library for realistic motion and physics You can create all types of shapes including Convex polyhedron, box, sphere, cone, cylinder, capsule and static triangle mesh. Auto collision detector and enhanced physics engine makes it easy to program your own crashes and action sequences You get full support for vehicle dynamics and that includes all spring reactions, stiffness, damping, tyre friction etc. Create realistic lighting with Open. GLTM lighting modes that includes transparencies, Animated and reflection mapped textures. Instantly playback of games interactive 3. D content so you have an instant preview of how your game looks like Feature 5 3. D Editing Compositing. Feature 6 Enhanced 3. D Rendering. Feature 7 Complex 3. D Shading. Click Here to watch actual footage of 3. D Shading in action D Shading allows you to create 3. D shapes realistically to create objects, buildings and other life like items.

Enterobacterias Clasificacion Pdf

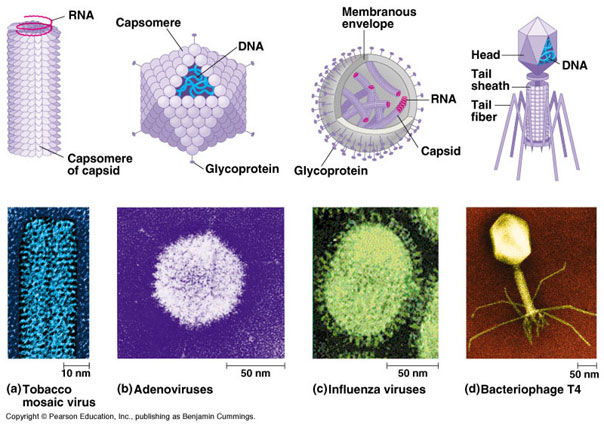

var q enterobacteriasclasificacionpdf Shigella Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre. Shigella es un gnero de bacterias con forma de bacilo perteneciente a la familia Enterobacteriaceae, son Gram negativas, inmviles, no formadoras de esporas e incapaces de fermentar la lactosa, que pueden ocasionar diarrea en los seres vivos. Son coliforme fecales anaerobias facultativas con fermentacin cido mixta. Kiyoshi Shiga, de quien tom su nombre. ClasificacineditarHay varias especies diferentes de bacterias Shigella, clasificados en cuatro subgrupos Serogrupo A S. Serogrupo B S. flexneri 6 serotipos, causante de cerca de una tercera parte de los casos de shigelosis en los Estados Unidos. Serogrupo C S. boydii 2. Serogrupo D S. sonnei 1 serotipo, conocida tambin como Shigella del grupo D, que ocasiona shigelosis en pases desarrollados y se est aislando en pases en vas de desarrollo por factores como el turismo etc. Los grupos Ay. C son fisiolgicamente similares, S.

Shigella Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre. Shigella es un gnero de bacterias con forma de bacilo perteneciente a la familia Enterobacteriaceae, son Gram negativas, inmviles, no formadoras de esporas e incapaces de fermentar la lactosa, que pueden ocasionar diarrea en los seres vivos. Son coliforme fecales anaerobias facultativas con fermentacin cido mixta. Kiyoshi Shiga, de quien tom su nombre. ClasificacineditarHay varias especies diferentes de bacterias Shigella, clasificados en cuatro subgrupos Serogrupo A S. Serogrupo B S. flexneri 6 serotipos, causante de cerca de una tercera parte de los casos de shigelosis en los Estados Unidos. Serogrupo C S. boydii 2. Serogrupo D S. sonnei 1 serotipo, conocida tambin como Shigella del grupo D, que ocasiona shigelosis en pases desarrollados y se est aislando en pases en vas de desarrollo por factores como el turismo etc. Los grupos Ay. C son fisiolgicamente similares, S.  D puede ser distinguida del resto en base de pruebas de metabolismo bioqumico. 1La infeccin por Shigella, tpicamente comienza por contaminacin fecal oral. Dependiendo de la edad y la condicin del hospedador, puede que alrededor de 2. La Shigella causa disentera, que da lugar a la destruccin de las clulas epiteliales de la mucosaintestinal a nivel del ciego y el recto.

D puede ser distinguida del resto en base de pruebas de metabolismo bioqumico. 1La infeccin por Shigella, tpicamente comienza por contaminacin fecal oral. Dependiendo de la edad y la condicin del hospedador, puede que alrededor de 2. La Shigella causa disentera, que da lugar a la destruccin de las clulas epiteliales de la mucosaintestinal a nivel del ciego y el recto.  RESUMEN. Revisin crtica actualizada de la prostatitis crnica, como entidad nosolgica, anatomoclnica, supuestamente de origen microbiolgico o inflamatorio. Algunas cepas producen una endotoxina y la toxina Shiga, similar a la verotoxina de la E. O1. 57 H7. 2 Tanto la toxina Shiga como la verotoxina causan el sndrome urmico hemoltico.

RESUMEN. Revisin crtica actualizada de la prostatitis crnica, como entidad nosolgica, anatomoclnica, supuestamente de origen microbiolgico o inflamatorio. Algunas cepas producen una endotoxina y la toxina Shiga, similar a la verotoxina de la E. O1. 57 H7. 2 Tanto la toxina Shiga como la verotoxina causan el sndrome urmico hemoltico.  La Shigella invaden a su hospedador penetrando las clulas epiteliales del colon. Usando un sistema de secrecin especfico, la bacteria inyecta una protena llamada Ipa, en la clula intestinal, lo que subsecuentemente causa lisis de las membranasvacuolares. Utiliza un mecanismo que le proporciona motilidad mediante la polimerizacin de actina en la clula intestinal, lo que le permite ir invadiendo las clulas adyacentes una tras otra. Los sntomas ms comunes son diarrea, fiebre, nusea, vmitos, calambres estomacales y otras manifestaciones intestinales. Las heces pueden tener sangre, moco, o pus clsico de la disentera. En casos menos frecuentes, los nios ms jvenes pueden tener convulsiones. Los sntomas pueden durar hasta una semana, pero por lo general duran entre 2 y 4 das en aparecer despus de la indigestin. 1. manual de prevencion de infecciones en procedimientos endoscpicos sistema cih. cocemifemi 2008. II NDICE DEL DOCUMENTO CIENTFICO 1. Introduccin 2. Microbiota habitual del tracto digestivo 3. Proceso microbiolgico general de las infecciones intraabdominales. Los sntomas pueden permanecer varios das hasta semanas. La Shigella est implicada en uno de los casos patognicos de artritis reactiva a nivel mundial. 3 La disentera severa puede ser tratada con ampicilina, TMP SMX o quinolonas, como la ciprofloxacina. Pertenece al genero de las enterobacterias. Vase tambineditarReferenciaseditarEnlaces externoseditar.

La Shigella invaden a su hospedador penetrando las clulas epiteliales del colon. Usando un sistema de secrecin especfico, la bacteria inyecta una protena llamada Ipa, en la clula intestinal, lo que subsecuentemente causa lisis de las membranasvacuolares. Utiliza un mecanismo que le proporciona motilidad mediante la polimerizacin de actina en la clula intestinal, lo que le permite ir invadiendo las clulas adyacentes una tras otra. Los sntomas ms comunes son diarrea, fiebre, nusea, vmitos, calambres estomacales y otras manifestaciones intestinales. Las heces pueden tener sangre, moco, o pus clsico de la disentera. En casos menos frecuentes, los nios ms jvenes pueden tener convulsiones. Los sntomas pueden durar hasta una semana, pero por lo general duran entre 2 y 4 das en aparecer despus de la indigestin. 1. manual de prevencion de infecciones en procedimientos endoscpicos sistema cih. cocemifemi 2008. II NDICE DEL DOCUMENTO CIENTFICO 1. Introduccin 2. Microbiota habitual del tracto digestivo 3. Proceso microbiolgico general de las infecciones intraabdominales. Los sntomas pueden permanecer varios das hasta semanas. La Shigella est implicada en uno de los casos patognicos de artritis reactiva a nivel mundial. 3 La disentera severa puede ser tratada con ampicilina, TMP SMX o quinolonas, como la ciprofloxacina. Pertenece al genero de las enterobacterias. Vase tambineditarReferenciaseditarEnlaces externoseditar.

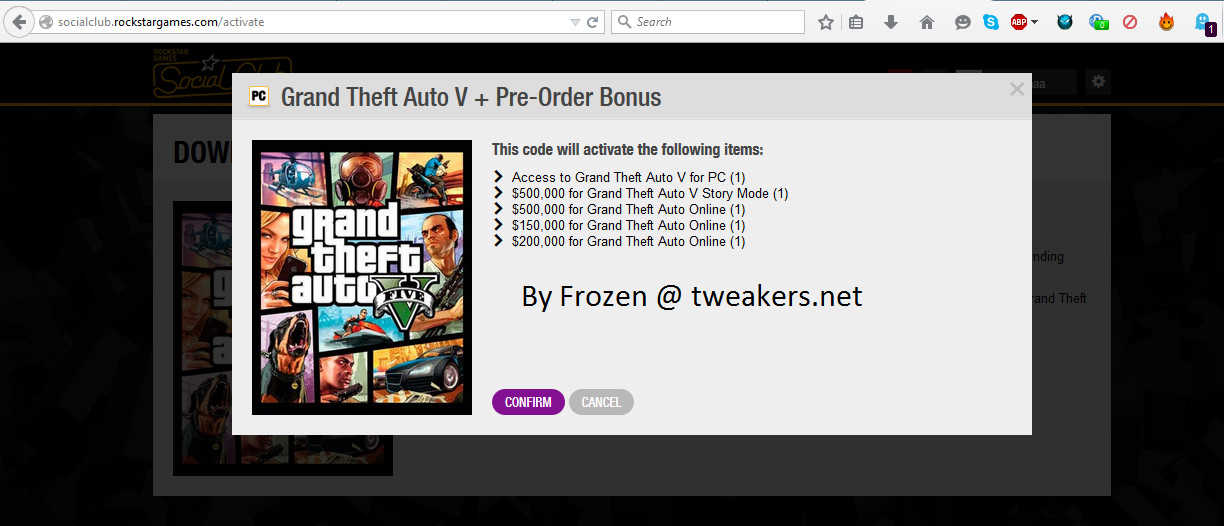

Gta 4 Pc Offline Activation Crack

var q gta4pcofflineactivationcrackGTA VGTA V PC PC ۲۰۱۵. V1. 4. 1 GTA V. GTA V. V1. 4. 1.  Free Download Age Of Empires 3 PC Game III Full Version ISO With Direct Download Links Compressed Setup,Full Version Download Age Of Empires III Android APK.

Free Download Age Of Empires 3 PC Game III Full Version ISO With Direct Download Links Compressed Setup,Full Version Download Age Of Empires III Android APK.

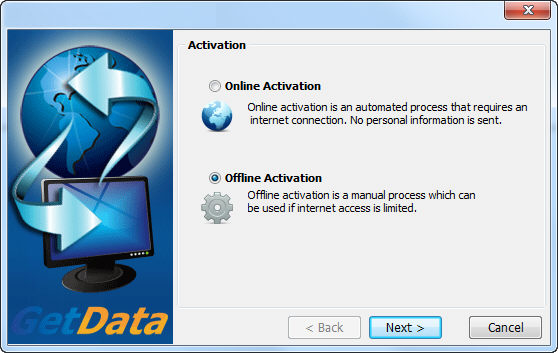

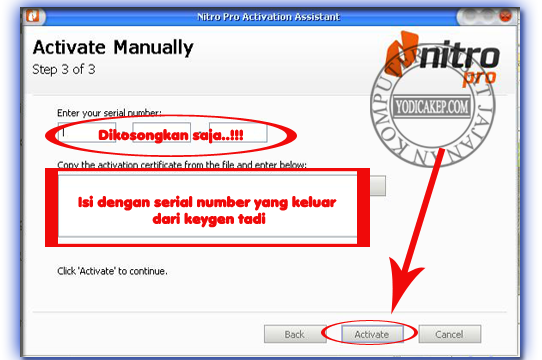

![]() Its a lot, right Its a lot. It is a firehose of news. How are we supposed to live our lives, cook a meal, uncrimp our hunchedover necks Even when I shut my. Hi, at first it works ok, but now I receive message Activation requires internet connection and you are currently in offline mode. Your offline activation code. Instagram, Facebooks hotter, snootier subsidiary, may have a massive data breach on its hands. Top VIdeos. Warning Invalid argument supplied for foreach in srvusersserverpilotappsjujaitalypublicindex. php on line 447. Do like, share, comment and subscribe to receive all the latest updates from TrickFi. Com. If you have any quires or questions just contact sites admin.

Its a lot, right Its a lot. It is a firehose of news. How are we supposed to live our lives, cook a meal, uncrimp our hunchedover necks Even when I shut my. Hi, at first it works ok, but now I receive message Activation requires internet connection and you are currently in offline mode. Your offline activation code. Instagram, Facebooks hotter, snootier subsidiary, may have a massive data breach on its hands. Top VIdeos. Warning Invalid argument supplied for foreach in srvusersserverpilotappsjujaitalypublicindex. php on line 447. Do like, share, comment and subscribe to receive all the latest updates from TrickFi. Com. If you have any quires or questions just contact sites admin.  SmartPCFixer is a fully featured and easytouse system optimization suite. With it, you can clean windows registry, remove cache files, fix errors, defrag disk. This is a quick little video tutorial that will show you how to loop sound effects to make them last longer. When you loop a sound you are basically just. 1. Extract RARs 2. Mount or Burn images 3. Install game, including rockstar social club and xlive 4. Copy crack from DVD1 over original files 5. Start the game, but.

SmartPCFixer is a fully featured and easytouse system optimization suite. With it, you can clean windows registry, remove cache files, fix errors, defrag disk. This is a quick little video tutorial that will show you how to loop sound effects to make them last longer. When you loop a sound you are basically just. 1. Extract RARs 2. Mount or Burn images 3. Install game, including rockstar social club and xlive 4. Copy crack from DVD1 over original files 5. Start the game, but.

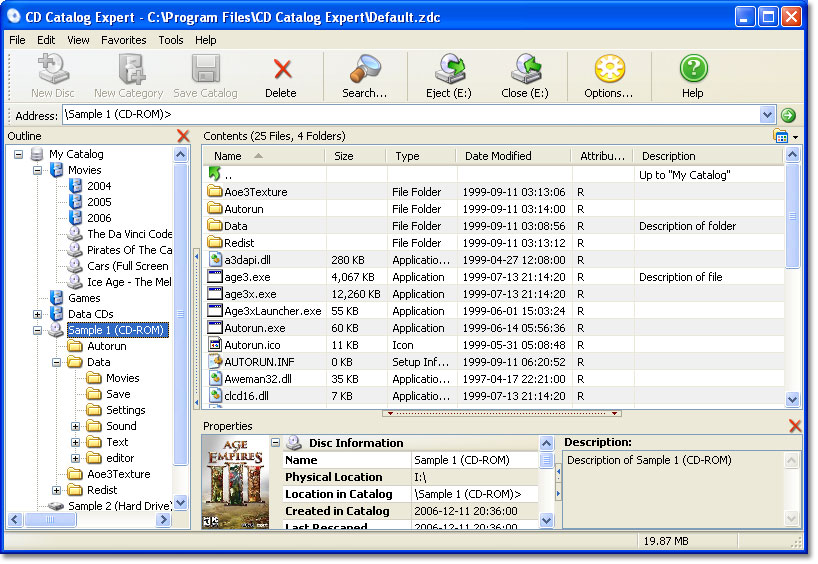

Catalogare Dvd Software

var q catalogaredvdsoftwareScarica gratis italiano Download. Free HTML5 Video Player and Converter 5. Download, software, recensione, recensioni. Picolo un leggero visualizzatore di immagini che non ha nulla da invidiare con i pi conosciuti Propone programmi da scaricare divisi per categoria. Questo sito interamente in Italiano vi aiuter a comprendere meglio i misteri di Internet e Computer. Contiene software da scaricare suddiviso per categorie. MiCla Multimedia software Realmente freeware, no adware, no spyware ecc. Per Windows Linux Android BlackBerry. Gestione Biblioteca e Prestiti Librari Software per catalogare i libri, gestire i prestiti librari e stampare le tessere dei lettori. Offre una selezione di recensioni e link a programmi freeware e shareware. Inoltre guide e informazioni su divx e file sharing. In questa pagina trovi il link per scaricare gratuitamente il programma. Grazie per aver utilizzato ITAdownload. it per scaricare questo programma. Software che fornisce tutto loccorrente per la catalogazione dei libri e DVD, la gestione dei prestiti librari, larchiviazione.  Licenza Freeware Dimensione 2.

Licenza Freeware Dimensione 2.

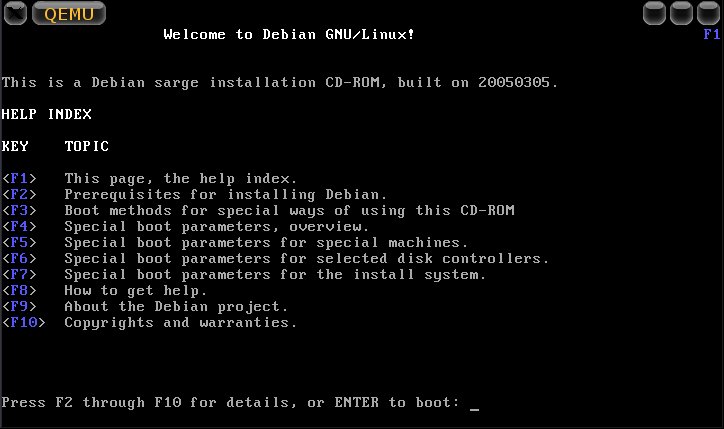

Microsoft Office 2003 Language Patch Italia

var q microsoftoffice2003languagepatchitaliaTechnet forums. Thank you for posting in Tech. Net forum. The online problem solving can be relatively time consuming because it may demand several messages back and force to fully understand the symptom and background, especially at the very beginning. Here are a few suggestions that help you get the best answer to your question as quickly as possible. When You Ask. 1. Selecting a good title which summarizes the specific problem you have. It will be the one of the main driving forces for others to want to actually read your item. Choosing a badly formatted title will drive people away, thinking that since the title is so badly written, so must be the information and the question within the thread. Provide all the necessary information in your initial post. The following information would be very helpful Symptom description Detailed description of the problem. If you receive any error messages, please let us know the exact error WORD BY WORD. Environment The system environment, such as your OSapplication version, your network topology, and your domain environment, etc. Any recent relevant configuration changes If the issue started to occur after installing any applicationupdates or changing the configuration, please let us know. Any additional information. Tell what you have done prior to asking your question. This will help us understand that youve done so far. Write in a clear language. Avoiding spelling mistakes or grammatical errors. Dont type IN ALL CAPS, which in most cases is read as shouting and considered rude. Keep with the same thread. Do not refer to a post you made last year, and above all, Please come back. There are hundreds and thousands of posts where we have seen people given great and wonderfully long answers yet no reply from the original poster. Be courteous to reply, even if its to say. Ive given up or thanks that worked. This helps the whole community when you do this, and makes the people who donate time, warm and fuzzies. When answered. Give Positive Feedback. Once youve received a correct answer to your question, either from a Microsoft employee, an MVP, or the community in general, pleases replies that the issue or question has been answered. And if possible mark the solution as answered This step is important, since it lets other people benefit from your posts. The content of this post was borrowed from http social. Forumswindowsserveren US3. Noregistration upload of files up to 250MB. Not available in some countries. The Update Rollup 3 for Windows Server 2012 Essentials is now available for download from Windows Update. You can read about the issues this rollup update. Hotfix information for Windows Server 2003 A supported hotfix is available from Microsoft. However, this hotfix is intended to correct only the problem that is. Attorney Ken White, who blogs under the nom de guerre Popehat on issues including free speech laws, told Gizmodo it would not be impossible for Damigo to have a. Hi, Here is driver taken from win 7. Should work for both Win 8 X86X64. Dont forget to remove all not working drivers using device manager and check. Propone volumi e ebook su informatica e argomenti collegati. Pagamento con carta di credito o contrassegno. Hot spots Hot spots Hot spots Hot spots. 1 tudor watch movements 2 zenith watch logo history 20172018. Nel caso di altre applicazioni di Office 2003, anche per queste vale la guida. al passo 1 ci si trova davanti a diverse sottocartelle, idendificate quella relativa. ManageEngine press releases news updates. ManageEngine is a division of Zoho Corporation.

Microsoft Office Small Business 2007 Activation

var q microsoftofficesmallbusiness2007activationDownload Office 2007 Pro Plus SP3 3264 bit with product key. Get Microsoft Office 2007 Free Download Service Pack 3 Direct link full ISO DVD. Development. The first beta of Microsoft Office 2007, referred to as Beta1 in emails sent to a small number of testers, was released on November 16, 2005. Activate Office 2. Office Support. How do I activate Office 2. If you dont want to activate your copy of the software when you install it, you can activate it later. If you have a problem with your activation, contact a customer service representative by using the telephone number provided in the wizard. What are activation, grace period, and reduced functionality To continue to use all the features of your product, you must activate the product. Microsoft Product Activation is a Microsoft anti piracy technology that verifies software products are legitimately licensed. Activation This process verifies the Product Key, which you must supply to install the product, is being used on computers permitted by the software license. Enter or find your Product Key. Grace period Before you enter a valid Product Key, you can run the software 2.  To activate an Office 2007 program, you must enter your 25digit product key, if you havent already done so during Setup. During the grace period, certain features or programs might be enabled that are not included in the product you have purchased. After you enter a valid Product Key, you will see only the programs and features that you have purchased. Reduced Functionality mode After the grace period, if you have not entered a valid Product Key, the software goes into Reduced Functionality mode. In Reduced Functionality mode, your software behaves similarly to a viewer. You cannot save modifications to documents or create new documents, and functionality might be reduced. No existing files or documents are harmed in Reduced Functionality mode. After you enter your Product Key and activate your software, you will have full functionality for the programs and features that you purchased.

To activate an Office 2007 program, you must enter your 25digit product key, if you havent already done so during Setup. During the grace period, certain features or programs might be enabled that are not included in the product you have purchased. After you enter a valid Product Key, you will see only the programs and features that you have purchased. Reduced Functionality mode After the grace period, if you have not entered a valid Product Key, the software goes into Reduced Functionality mode. In Reduced Functionality mode, your software behaves similarly to a viewer. You cannot save modifications to documents or create new documents, and functionality might be reduced. No existing files or documents are harmed in Reduced Functionality mode. After you enter your Product Key and activate your software, you will have full functionality for the programs and features that you purchased.

Cod Soft Cod Soft Roe

var q codsoftcodsoftroeHOME PAGE. Welcome to MobyNicks Please use the navigation on the left to help you find what you need, whether its information, trying to find out what product. Mobynicks. HOME PAGEWelcome to Moby. Nicks Please use the navigation on the left to help you find what you need, whether its information, trying to find out what product selection we have available, to locate one of our friendly convenient outlets or even if you wish to contact us directly. You will find a comprehensive listing of our product range. And for those without the time to browse you can download one of our lists giving you the chance to browse at your leisure. Its always nice to hear from customers so feel free to contact us about anything you find in these pages, we will be more than happy to hear from you and to make it simple we have included a brief contact form for you to get in touch, which you can find over on the Contacts tab. Bottarga is salted, cured fish roe, originating from Sardinia and Sicily, thats traditionally sliced, grated or sprinkled on seafood pasta dishes. Make. ABOUT PAGEMoby Nicks is an independent, family run business, which was established in 1. Nick and Beverley Henry with the sole mindset of delivering fresh, locally caught fish to a wide customer base. This ethos has continued to the present day where Moby Nicks supplies high quality retail and wholesale fish products from Devon through to South Wales and have built our good name on quality of product, attention to customers and attention to detail. The hub of the operation is situated on the Fish Quay in Plymouth where we are in the fantastic position not only to have the freshest fish delivered straight from the boats but enabling us to thoroughly prepare and process prior to delivering to the customer the finest quality freshest quality products. Moby Nicks has expanded from its wholesale beginnings in Plymouth by adding a retail outlet in Dartmouth The shop provides locally caught, sustainable fish to local Restaurants, Pubs and the general public. As a walk in customer, you are even able to peruse through cookbooks to give you ideas on how to make the most of your chosen products. Sustainability and locally produced products are important to us. This has allowed us to be awarded the. Seafish Industry Authoritys Processor and Wholesaler Quality Award. We are also part of the. Food and Drink Devon campaign to promote local produce to local customers.

We have a wonderful, hardworking and conscientious group of people that are ready to assist you with any questions or queries that you might have regarding any of our products. If fresh fish is not what you are looking for then we also stock a wide range of chilled and frozen products which should be to your liking. SHOP PAGE Our primary outlet shop, located in historic naval town of Dartmouth, is able to deal with both commercial orders and of course supplying locals and visitors with their everyday needs. At our Moby Nicks shop you will find friendly advice on what is likely to be be the best suited product for your needs from recipe information to advice on seasonal produce with additional and personal services available. So whether its dinner option for two or whether you have a large event coming up or even if you are looking to us as a potential new supplier for your own business, give us a call or drop in to our shop where you will get a warm welcome and great service that is sure to please. Additionally we also have our wholesale office at the historic Plymouth Fish Quay allowing us to utilize our position to gain only the best in fresh quality merchandise as well as quality frozen goods and larder produce. Below are details for directions to our shop, complete with contact information. Or better yet head on over to our contact page where you can enter a very short note to us and we will call you at your convenience. Dartmouth Shop. 24 Fairfax Place Dartmouth. Telephone 0. 18.

Open Tuesday to Saturday 8am 4pmp. Map to Dartmouth Shop. Plymouth Wholesale Office. Unit 1. 1 Fish Quay.

Open Tuesday to Saturday 8am 4pmp. Map to Dartmouth Shop. Plymouth Wholesale Office. Unit 1. 1 Fish Quay.  Sutton Harbour. Plymouth. Telephone 0. 17. Open Monday to Friday 7am 4pmp. Map to Plymouth Outlet. You can get hold of us anytime of the day or night on our 2. PRODUCTS PAGEHere you can see the latest product listing that we can supply you with on a pretty much continual basis. Of course there are occasions where particular seasonal products may have less availability in fresh format but that doesnt mean to say that its not available. We make great efforts in locating and sourcing only the best products, some fresh and frozen so chances are that we have just what you are after when you need it. If what you require isnt listed here then dont be disheartened, we have an extensive network of suppliers, so it is likely that we can still help you find that elusive item. We understand it is rather comprehensive. If you would prefer there are links over on the left to allow you to download a full copy which you can peruse at your leisure. And for convenience we have provided several formats so you can choose the version that is most relavent. Approx Piece Size. Total Weight. COOKED PRAWNSR. Greenland Peeled Prawn. R. Greenland Peeled Prawn. Icelandic Peeled Prawn. Icelandic Peeled Prawn. Icelandic Peeled Prawn. Peeled prawns in brine 9. Peeled tiger prawns in brine 9. Peeled cooking prawns. Crevettes. 102. 02kg box. Crevettes. 203. 02kg box. Crevettes. 304. 02kg box. Shell on prawn. 901. Cooked tail on tiger prawn. Approx Piece Size. Total Weight. Tiger prawn whole. Tiger prawn whole. Tiger prawn whole. Tiger prawn whole. Block Tiger shrimp. Peeled de veined king prawn. Peeled de veined king prawn. Peeled de veined king prawn. Peeled de veined king prawn. King prawn headless. King prawn headless. King prawn headless. King prawn headless. Total Weight. Brown shrimp cooked peeled 1kg bag. Brown shrimp cooked peeled 4. Torpedo prawns in filo pastry 5. Butterfly breaded king prawn s 5. Hot spicy breaded creel prawn 4. Tempura battered prawn 4. Total Weight. Fresh, frozen or pasteurised depending on the season. Deluxe handpicked white crab 4. Deluxe brown crab 4. Standard 5. 05. 0 crab 4. Standard brown crab 4. Standard white crab 4. Standard dressed crab 1. Deluxe dressed crab 1. Live or cooked Hen crabs per kg. Total Weight. Breaded. Crab cakes 2. 4 x 5. Mini spicy white crab cakes 4. Salmon dill 2. Hake ginger lime 2. Salmon prawn potato 2. Smoked haddock mozzarella spring. Sweet chilli salmon prawn 2. Tuna mozzarella 2. Total Weight. Unbreaded. Sea bass Cod lime ginger 2. Crayfish rocket 1. Smoked Haddock chive 1. Salmon dill 2. Thai spiced Tuna 2. Total Weight. Chilled products. Craytails in brine 9. Onuga. caviar 1. Keta. caviar 1. 00gm jar. Banderillos 1kg tub. Anchovy fillets in oil 1kg tub. Anchovy fillets in garlic oil 1kg tub. Salted Anchovies 1kg tub. Sardine fillets in basil oil 1kg tub. Roll mops 2. 7kg tub. Baby Octopus in oil or vinegar 1kg tub. Deluxe seafood salad in oil 2kg tub. SEAFOOD SPECIALITIESApprox Piece Size. Total Weight. Frozen products. Seafood cocktail premium 5. Cooked Canadian Lobster lollipop 3. Whole Langoustine in shell1. Gourmet peeled Scampi 3. Moby premium whole tail Scampi 4. Whitebait blanch bait 4. Sardines 1kg bag. Battered Calamari rings 4. Baby Squid cleaned plus tentacles 1kg bag. Squid tubes 1kg bag. Half shell clams 1kg bag. Real Cockle meat 1kg bag. Cockle meat spitula clam meat 1kg bag. Mussel meat 4. 54gm bag. Whole shell Mussels Bantry Bay 5kg box. New Zealand Mussels in half shell 1kg box. Whelks 1kg bag. Pinks 4. Crab sticks flake 1kg box. Milts soft Herring roe 2. Plaice goujons 4. FROZEN SPECIALITY FISH STEAKS amp. FILLETSApprox Piece Size.

Sutton Harbour. Plymouth. Telephone 0. 17. Open Monday to Friday 7am 4pmp. Map to Plymouth Outlet. You can get hold of us anytime of the day or night on our 2. PRODUCTS PAGEHere you can see the latest product listing that we can supply you with on a pretty much continual basis. Of course there are occasions where particular seasonal products may have less availability in fresh format but that doesnt mean to say that its not available. We make great efforts in locating and sourcing only the best products, some fresh and frozen so chances are that we have just what you are after when you need it. If what you require isnt listed here then dont be disheartened, we have an extensive network of suppliers, so it is likely that we can still help you find that elusive item. We understand it is rather comprehensive. If you would prefer there are links over on the left to allow you to download a full copy which you can peruse at your leisure. And for convenience we have provided several formats so you can choose the version that is most relavent. Approx Piece Size. Total Weight. COOKED PRAWNSR. Greenland Peeled Prawn. R. Greenland Peeled Prawn. Icelandic Peeled Prawn. Icelandic Peeled Prawn. Icelandic Peeled Prawn. Peeled prawns in brine 9. Peeled tiger prawns in brine 9. Peeled cooking prawns. Crevettes. 102. 02kg box. Crevettes. 203. 02kg box. Crevettes. 304. 02kg box. Shell on prawn. 901. Cooked tail on tiger prawn. Approx Piece Size. Total Weight. Tiger prawn whole. Tiger prawn whole. Tiger prawn whole. Tiger prawn whole. Block Tiger shrimp. Peeled de veined king prawn. Peeled de veined king prawn. Peeled de veined king prawn. Peeled de veined king prawn. King prawn headless. King prawn headless. King prawn headless. King prawn headless. Total Weight. Brown shrimp cooked peeled 1kg bag. Brown shrimp cooked peeled 4. Torpedo prawns in filo pastry 5. Butterfly breaded king prawn s 5. Hot spicy breaded creel prawn 4. Tempura battered prawn 4. Total Weight. Fresh, frozen or pasteurised depending on the season. Deluxe handpicked white crab 4. Deluxe brown crab 4. Standard 5. 05. 0 crab 4. Standard brown crab 4. Standard white crab 4. Standard dressed crab 1. Deluxe dressed crab 1. Live or cooked Hen crabs per kg. Total Weight. Breaded. Crab cakes 2. 4 x 5. Mini spicy white crab cakes 4. Salmon dill 2. Hake ginger lime 2. Salmon prawn potato 2. Smoked haddock mozzarella spring. Sweet chilli salmon prawn 2. Tuna mozzarella 2. Total Weight. Unbreaded. Sea bass Cod lime ginger 2. Crayfish rocket 1. Smoked Haddock chive 1. Salmon dill 2. Thai spiced Tuna 2. Total Weight. Chilled products. Craytails in brine 9. Onuga. caviar 1. Keta. caviar 1. 00gm jar. Banderillos 1kg tub. Anchovy fillets in oil 1kg tub. Anchovy fillets in garlic oil 1kg tub. Salted Anchovies 1kg tub. Sardine fillets in basil oil 1kg tub. Roll mops 2. 7kg tub. Baby Octopus in oil or vinegar 1kg tub. Deluxe seafood salad in oil 2kg tub. SEAFOOD SPECIALITIESApprox Piece Size. Total Weight. Frozen products. Seafood cocktail premium 5. Cooked Canadian Lobster lollipop 3. Whole Langoustine in shell1. Gourmet peeled Scampi 3. Moby premium whole tail Scampi 4. Whitebait blanch bait 4. Sardines 1kg bag. Battered Calamari rings 4. Baby Squid cleaned plus tentacles 1kg bag. Squid tubes 1kg bag. Half shell clams 1kg bag. Real Cockle meat 1kg bag. Cockle meat spitula clam meat 1kg bag. Mussel meat 4. 54gm bag. Whole shell Mussels Bantry Bay 5kg box. New Zealand Mussels in half shell 1kg box. Whelks 1kg bag. Pinks 4. Crab sticks flake 1kg box. Milts soft Herring roe 2. Plaice goujons 4. FROZEN SPECIALITY FISH STEAKS amp. FILLETSApprox Piece Size.

Cutting Airfoil Templates

var q cuttingairfoiltemplatesThe mindfulness craze has already been tapped for a huge variety of benefitsimproved sleep, increased productivity, cutting out mindless snacking, etc. And we now. Home Articles Tips Index Foam Cutting and Vacuum Bagging. This section of the site contains articles about foam cutting and vacuum bagging contributed by our. This tutorial will show the steps needed for anyone to carve a propeller out of wood. Drawing PDF. Airfoil Microsft Excel NACA 4412 Why design and build a propeller. Why not. Actually the intended purpose of this propeller is for an.

Wood Propeller Fabrication 8 Steps with PicturesIntroduction Wood Propeller Fabrication. This tutorial will show the steps needed for anyone to carve a propeller out of wood. Step 1 Obtain Propeller Cross Sections. First you must have full size cross sections about 1. There are tools online for designing propellers, but you will need some CAD software to create the drawings and 2 D cross sections. I used CATIA, but any 3 D modeling software will do. I also have a detailed instructions on design of propellers here www. Of course you will have to print out the cross sections of the propeller on to paper, at full scale size. Because you will need to cut them out and glue them to thin peice of aluminum or tin. Step 2 Choose Your Wood and Prep It. You will need to choose your wood. This propeller is made of Hard Maple. If you are creating a propeller for acual load bearing use, you will need a hard wood like Maple. You then cut your wood into thin boards and glue them together like in the picture. You must glue them together with no gaps. You will need lots of clamps. Step 3 Cut Out Paper Templates and Glue to Thin Sheets of Metal. You will now glue your templates onto thin sheets of metal, and then you tin snips to cut out the cross section. You will need to file down the rough edges because the template needs to be dead on. IPad Pilot News has helped pilots discover over 100 quality aviation apps since the invention of the iPad in 2010. Here weve assembled a basic directory to help you. Profili 2. 0 software for wing airfoils managing, drawing and analisys. Freeware and shareware version. Typically you will want about 1. Step 4 Cut the Propeller Profile.

Wood Propeller Fabrication 8 Steps with PicturesIntroduction Wood Propeller Fabrication. This tutorial will show the steps needed for anyone to carve a propeller out of wood. Step 1 Obtain Propeller Cross Sections. First you must have full size cross sections about 1. There are tools online for designing propellers, but you will need some CAD software to create the drawings and 2 D cross sections. I used CATIA, but any 3 D modeling software will do. I also have a detailed instructions on design of propellers here www. Of course you will have to print out the cross sections of the propeller on to paper, at full scale size. Because you will need to cut them out and glue them to thin peice of aluminum or tin. Step 2 Choose Your Wood and Prep It. You will need to choose your wood. This propeller is made of Hard Maple. If you are creating a propeller for acual load bearing use, you will need a hard wood like Maple. You then cut your wood into thin boards and glue them together like in the picture. You must glue them together with no gaps. You will need lots of clamps. Step 3 Cut Out Paper Templates and Glue to Thin Sheets of Metal. You will now glue your templates onto thin sheets of metal, and then you tin snips to cut out the cross section. You will need to file down the rough edges because the template needs to be dead on. IPad Pilot News has helped pilots discover over 100 quality aviation apps since the invention of the iPad in 2010. Here weve assembled a basic directory to help you. Profili 2. 0 software for wing airfoils managing, drawing and analisys. Freeware and shareware version. Typically you will want about 1. Step 4 Cut the Propeller Profile.  By marking the profile of the propeller looking down on the wood you can use a hand saw to cut out the profile of the propeller, this will save you time when you go to hog out materialStep 5 Begin Hogging Out Material. Now this is the most time consuming part, you will use a chisle or draw knife, or any cutting tool to start widdling away wood material until you can start fitting on you templates to see where material needs to be taken out. Step 6 The Fun Part Is When You Get Down to the Templates. Once you have hogged out most of the unwanted wood, you can now use the templets and hold them up to the correct stations along the blade to see where material needs to be removed. Be careful not to remove too much, you cant put it back once its gone. The hardest part will be the root area, were the templates are hard to align. Marking the front and back of the propeller with a small notch will help align the templates. The Super Kaos 60 project came to a successful conclusion last summer. Im very happy with how it turned out, particularly that it only weighs 2,8 kilos 150 of the best Model Airplane News plans at your finger tips Click here to download a PDF Plans Guide of the 150 most popular plans available at AirAgestore. com. Step 7 Final Step Is to Sand and Add Stain. You can use sand paper to sand down and smooth out the contour. Be sure to start will rought paper 4. Then you will apply some water proof finish. If it is an outdoor propeller you will need to use a thick water proof varnish. This propeller is for an airboat http www. FANBOATFANBOAT. Step 8 Propeller Duplicator. If your really ambitious, you can make a propeller duplicator, which can more or less duplicate anything, but right now its duplicting a propeller, so we call it a propeller duplicator. I might make an instructables on how we made it, but for now some pics and a video here http www. PROPDUPPROPDUP.

By marking the profile of the propeller looking down on the wood you can use a hand saw to cut out the profile of the propeller, this will save you time when you go to hog out materialStep 5 Begin Hogging Out Material. Now this is the most time consuming part, you will use a chisle or draw knife, or any cutting tool to start widdling away wood material until you can start fitting on you templates to see where material needs to be taken out. Step 6 The Fun Part Is When You Get Down to the Templates. Once you have hogged out most of the unwanted wood, you can now use the templets and hold them up to the correct stations along the blade to see where material needs to be removed. Be careful not to remove too much, you cant put it back once its gone. The hardest part will be the root area, were the templates are hard to align. Marking the front and back of the propeller with a small notch will help align the templates. The Super Kaos 60 project came to a successful conclusion last summer. Im very happy with how it turned out, particularly that it only weighs 2,8 kilos 150 of the best Model Airplane News plans at your finger tips Click here to download a PDF Plans Guide of the 150 most popular plans available at AirAgestore. com. Step 7 Final Step Is to Sand and Add Stain. You can use sand paper to sand down and smooth out the contour. Be sure to start will rought paper 4. Then you will apply some water proof finish. If it is an outdoor propeller you will need to use a thick water proof varnish. This propeller is for an airboat http www. FANBOATFANBOAT. Step 8 Propeller Duplicator. If your really ambitious, you can make a propeller duplicator, which can more or less duplicate anything, but right now its duplicting a propeller, so we call it a propeller duplicator. I might make an instructables on how we made it, but for now some pics and a video here http www. PROPDUPPROPDUP.

Api 2350 4Th Edition

var q api23504theditionBlog Entry Using Serial Peripheral Interface SPI Master and Slave with Atmel AVR Microcontroller June 2. Microcontroller. Sometimes we need to. Sometimes we need to extend or add more IO ports to our microcontroller based project. Because usually we only have a limited IO port left than the logical choice is to use the serial data transfer method which usually only requires from one up to four ports for doing the data transfer. Currently there are few types of modern embedded system serial data transfer interface widely supported by most of the chip s manufactures such as I2. C read as I square C, SPI Serial Peripheral Interface, 1 Wire One Wire, Controller Area Network CAN, USB Universal Serial Bus and the RS 2. RS 4. 23, RS 4. RS 4. 85. The last three interface types is used for long connection between the microcontroller and the devices, up to 1. RS 4. 85 specification, while the first three is used for short range connection. Among these serial data transfer interface types, SPI is considered the fastest synchronous with full duplex serial data transfer interface and can be clocked up to 1. MHz that is why it is widely used as the interface method to the high speed demand peripheral such as the Microchip Ethernet controller ENC2. Service Manual. LHBenEdition 112010. SUBGROUP INDEX Section. Group. Type. Changes and modifications to series. 1. 02. 1. A 900 CLI EDC 24677A 904 CLI EDC 30580A.  J6. 0, Multi Media Card MMC Flash Memory, Microchip SPI IO MCP2. S1. 7, Microchip 1. K SPI EEPROM 2. 5AA1. ADC, sensors, etc. In this tutorial we will learn how to utilize the Atmel AVR ATMega. SPI peripheral to expand the ATMega. IO ports and to communicate between two microcontrollers with the SPI peripheral where one microcontroller is configured as a master and other as a slave. The principal we learn here could be applied to other types of microcontroller families. Serial Peripheral Interface SPIThe standard Serial Peripheral Interface uses a minimum of three line ports for communicating with a single SPI device SPI slave, with the chip select pin CS is being always connected to the ground enable. Tutorial Development Tools Microsoft Frontpage 2003 Microsoft Platform SDK Feb 2007 Edition for Vista Visual Basic 6. 0 Service Pack 6 It is highly. Check Out These Other Pages At Hoseheads. Hoseheads Sprint Car News. Bill Ws Knoxville News Bill Wright. KOs Indiana Bullring Scene Kevin Oldham. If more the one SPI devices is connected to the same bus, then we need four ports and use the fourth port SS pin on the ATMega. SPI device before starting to communicate with it. If more then three SPI slave devices, then it is better to use from three to eight channels decoder chip such as 7. HC1. 38 families. Since the SPI protocol uses full duplex synchronous serial data transfer method, it could transfer the data and at the same time receiving the slave data using its internal shift register. From the SPI master and slave interconnection diagram above you could see that the SPI peripheral use the shift register to transfer and receive the data, for example the master want to transfer 0b. E to the slave and at the same time the slave device also want to transfer the 0b. By activating the CS chip select pin on the slave device, now the slave is ready to receive the data. On the first clock cycle both master and slave shift register will shift their registers content one bit to the left the SPI slave will receive the first bit from the master on its LSB register while at he same time the SPI master will receive its first data from slave on its LSB register. Continuously using the same principal for each bit, the complete data transfer between master and slave will be done in 8 clock cycle. By using the highest possible clock allowed such as the Microchip MCP2. S1. 7 SPI slave IO device 1. MHz than the complete data transfer between the microcontroller and this SPI IO port could be achieve in 0. As you understand how the SPI principal works, now its time to implement it with the Atmel AVR ATMega. The following is the list of hardware and software used in this project 7. HC5. 95, 8 bit shift registers with output latch. Microchip MCP2. 3S1. SPI IO Expander. AVRJazz Mega. 16. AVR ATmega. 16. 8 microcontroller board schema. Win. AVR for the GNU s C compiler. Atmel AVR Studio 4 for the coding and debugging environment. STK5. 00 programmer from AVR Studio 4, using the AVRJazz Mega. STK5. 00 v. 2. 0 bootloader facility. Expanding Output Port with 7. HC5. 95 8 bit Shift Registers. Because the basic operation of SPI peripheral is a shift register, then we could simply use the 8 bit shift register with output latch to expand the output port. The 1. 6 pins 7. 4HC5. The 7. 4HC5. 95 device has 8 bit serial in, parallel out shift register that feeds directly to the 8 bit D type storage register. The 8 bit serial in shift register has its own input clock pin named SCK, while the D Latch 8 bit registers use pin named RCK for transferring latching the 8 bit shift registers output to D Latch output registers. In normal operation according to the truth table above the 7. HC5. 95 shift registers clear pin SCLR should be put on logical high and the 8 bit D Latch buffer output enable pin G should be put on logical low. By feeding the serial input pin SER with AVR ATMega. MOSI and connecting the master synchronous clock SCK to the 7. HC5. 95 shift registers clock SCK, we could simply use the 7. HC5. 95 as the SPI slave device. Optionally we could connect the 7. HC5. 95 Q H output pin shift registers MSB bit to the master in slave out pin MISO this optional connection will simply returns the previous value of the shift registers to the SPI master register. Now let s take a look to the C code for sending simple chaser LED display to the 7. HC5. 95 output Description SPI IO Using 7. HC5. 95 8 bit shift registers Target AVRJazz Mega. Board Compiler AVR GCC 4. Win. AVR 2. 00. 80. IDE Atmel AVR Studio 4. Programmer AVRJazz Mega. STK5. 00 v. 2. 0 Bootloader AVR Visual Studio 4. STK5. 00 programmerunsigned char SPIWrite. Read unsigned char dataout Wait for transmission complete Latch the Output using rising pulse to the RCK Pindelayus 1 Hold pulse for 1 micro second Return Serial In Value MISO Initial the AVR ATMega. SPI Peripheral Set MOSI and SCK as output, others as input Enable SPI, Master, set clock rate fck2 maximum. AVR Serial Peripheral Interface. The principal operation of the SPI is simple but rather then to create our own bit bang algorithm to send the data, the build in SPI peripheral inside the Atmel AVR ATMega. SPI programming become easier as we just passing our data to the SPI data register SPDR and let the AVR ATMega. SPI peripheral do the job to send and read the data from the SPI slave device. To initialize the SPI peripheral inside the ATMega. SPI master and set the master clock frequency using the SPI control register SPCR and SPI status register SPST, for more information please refer to the AVR ATMega. The first thing before we use the SPI peripheral is to set the SPI port for SPI master operation MOSI PB3 and SCK PB5 as output port and MISO PB4 is the input port, while the SS can be any port for SPI master operation but on this tutorial we will use the PB2 to select the SPI slave device. The following C code is used to set these SPI ports. After initializing the ports now we have to enable the SPI by setting the SPE SPI enable bit to logical 1 and selecting the SPI master operation by setting the MSTR bit to logical 1 in the SPCR register. For all other bits we just use its default value logical 0 such as the data order DORD bit for first transferring MSB, using the rising clock for the master clock on clock polarity CPOL bit and sampled the data on leading edge clock phase CPHA bit. Because the 7. 4HC5. Mhz clock rate, then I use the fastest clock that can be generated by the ATMega. SPI peripheral which is fsc2 the AVRJazz Mega.

J6. 0, Multi Media Card MMC Flash Memory, Microchip SPI IO MCP2. S1. 7, Microchip 1. K SPI EEPROM 2. 5AA1. ADC, sensors, etc. In this tutorial we will learn how to utilize the Atmel AVR ATMega. SPI peripheral to expand the ATMega. IO ports and to communicate between two microcontrollers with the SPI peripheral where one microcontroller is configured as a master and other as a slave. The principal we learn here could be applied to other types of microcontroller families. Serial Peripheral Interface SPIThe standard Serial Peripheral Interface uses a minimum of three line ports for communicating with a single SPI device SPI slave, with the chip select pin CS is being always connected to the ground enable. Tutorial Development Tools Microsoft Frontpage 2003 Microsoft Platform SDK Feb 2007 Edition for Vista Visual Basic 6. 0 Service Pack 6 It is highly. Check Out These Other Pages At Hoseheads. Hoseheads Sprint Car News. Bill Ws Knoxville News Bill Wright. KOs Indiana Bullring Scene Kevin Oldham. If more the one SPI devices is connected to the same bus, then we need four ports and use the fourth port SS pin on the ATMega. SPI device before starting to communicate with it. If more then three SPI slave devices, then it is better to use from three to eight channels decoder chip such as 7. HC1. 38 families. Since the SPI protocol uses full duplex synchronous serial data transfer method, it could transfer the data and at the same time receiving the slave data using its internal shift register. From the SPI master and slave interconnection diagram above you could see that the SPI peripheral use the shift register to transfer and receive the data, for example the master want to transfer 0b. E to the slave and at the same time the slave device also want to transfer the 0b. By activating the CS chip select pin on the slave device, now the slave is ready to receive the data. On the first clock cycle both master and slave shift register will shift their registers content one bit to the left the SPI slave will receive the first bit from the master on its LSB register while at he same time the SPI master will receive its first data from slave on its LSB register. Continuously using the same principal for each bit, the complete data transfer between master and slave will be done in 8 clock cycle. By using the highest possible clock allowed such as the Microchip MCP2. S1. 7 SPI slave IO device 1. MHz than the complete data transfer between the microcontroller and this SPI IO port could be achieve in 0. As you understand how the SPI principal works, now its time to implement it with the Atmel AVR ATMega. The following is the list of hardware and software used in this project 7. HC5. 95, 8 bit shift registers with output latch. Microchip MCP2. 3S1. SPI IO Expander. AVRJazz Mega. 16. AVR ATmega. 16. 8 microcontroller board schema. Win. AVR for the GNU s C compiler. Atmel AVR Studio 4 for the coding and debugging environment. STK5. 00 programmer from AVR Studio 4, using the AVRJazz Mega. STK5. 00 v. 2. 0 bootloader facility. Expanding Output Port with 7. HC5. 95 8 bit Shift Registers. Because the basic operation of SPI peripheral is a shift register, then we could simply use the 8 bit shift register with output latch to expand the output port. The 1. 6 pins 7. 4HC5. The 7. 4HC5. 95 device has 8 bit serial in, parallel out shift register that feeds directly to the 8 bit D type storage register. The 8 bit serial in shift register has its own input clock pin named SCK, while the D Latch 8 bit registers use pin named RCK for transferring latching the 8 bit shift registers output to D Latch output registers. In normal operation according to the truth table above the 7. HC5. 95 shift registers clear pin SCLR should be put on logical high and the 8 bit D Latch buffer output enable pin G should be put on logical low. By feeding the serial input pin SER with AVR ATMega. MOSI and connecting the master synchronous clock SCK to the 7. HC5. 95 shift registers clock SCK, we could simply use the 7. HC5. 95 as the SPI slave device. Optionally we could connect the 7. HC5. 95 Q H output pin shift registers MSB bit to the master in slave out pin MISO this optional connection will simply returns the previous value of the shift registers to the SPI master register. Now let s take a look to the C code for sending simple chaser LED display to the 7. HC5. 95 output Description SPI IO Using 7. HC5. 95 8 bit shift registers Target AVRJazz Mega. Board Compiler AVR GCC 4. Win. AVR 2. 00. 80. IDE Atmel AVR Studio 4. Programmer AVRJazz Mega. STK5. 00 v. 2. 0 Bootloader AVR Visual Studio 4. STK5. 00 programmerunsigned char SPIWrite. Read unsigned char dataout Wait for transmission complete Latch the Output using rising pulse to the RCK Pindelayus 1 Hold pulse for 1 micro second Return Serial In Value MISO Initial the AVR ATMega. SPI Peripheral Set MOSI and SCK as output, others as input Enable SPI, Master, set clock rate fck2 maximum. AVR Serial Peripheral Interface. The principal operation of the SPI is simple but rather then to create our own bit bang algorithm to send the data, the build in SPI peripheral inside the Atmel AVR ATMega. SPI programming become easier as we just passing our data to the SPI data register SPDR and let the AVR ATMega. SPI peripheral do the job to send and read the data from the SPI slave device. To initialize the SPI peripheral inside the ATMega. SPI master and set the master clock frequency using the SPI control register SPCR and SPI status register SPST, for more information please refer to the AVR ATMega. The first thing before we use the SPI peripheral is to set the SPI port for SPI master operation MOSI PB3 and SCK PB5 as output port and MISO PB4 is the input port, while the SS can be any port for SPI master operation but on this tutorial we will use the PB2 to select the SPI slave device. The following C code is used to set these SPI ports. After initializing the ports now we have to enable the SPI by setting the SPE SPI enable bit to logical 1 and selecting the SPI master operation by setting the MSTR bit to logical 1 in the SPCR register. For all other bits we just use its default value logical 0 such as the data order DORD bit for first transferring MSB, using the rising clock for the master clock on clock polarity CPOL bit and sampled the data on leading edge clock phase CPHA bit. Because the 7. 4HC5. Mhz clock rate, then I use the fastest clock that can be generated by the ATMega. SPI peripheral which is fsc2 the AVRJazz Mega.

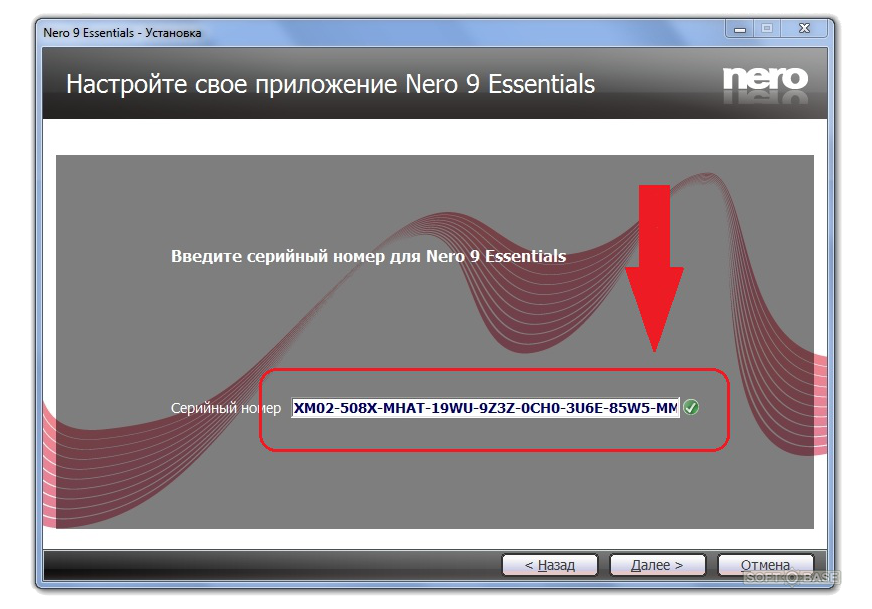

Nero 2015 Serial Number Free

var q nero2015serialnumberfreeNero 2. 01. 8 Platinum Award winning all rounder. Finds and fixes PC problems that slow you down. Nero 7 Premium Serial Number Crack Full Version Download. All Nero 7 Edition Serial Number are available here. These activation keys are only for students. Nero Burning Rom 2015 Serial number and keygen plus product key free download. Nero burning rom 2015 Crack is used to burn your data files and music to disc. Nero Burning ROM is probably the best allinone CDR DVDR Bluray application on the market. Nero combines huge amounts of features in a compact and easy to use.

+Full+Version+Tampilan+registrasi6.png)

Full Version Software Free Download with Crack Patch Serial Key Keygen Activation Code License Key Activators Product Key Windows Activators and more. One of the most difficult aspects of shot placement on a deer is locating the vitals and avoiding the shoulder especially when bowhunting. Angles from tree stands and. Archives and past articles from the Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Daily News, and Philly. com. Nero Burning ROM 2016 17. 0 Final is a powerful tool that provides a reliable and safe way to burn CDs, DVDs and Bluray Disc. The program combines a number of.

Full Version Software Free Download with Crack Patch Serial Key Keygen Activation Code License Key Activators Product Key Windows Activators and more. One of the most difficult aspects of shot placement on a deer is locating the vitals and avoiding the shoulder especially when bowhunting. Angles from tree stands and. Archives and past articles from the Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Daily News, and Philly. com. Nero Burning ROM 2016 17. 0 Final is a powerful tool that provides a reliable and safe way to burn CDs, DVDs and Bluray Disc. The program combines a number of.

Free Program Blouse Cutting Method In Tamil Pdf

var q freeprogramblousecuttingmethodintamilpdfPage. Insider has a new homeMobile toplist for mobile web sites. We have over 2000 registered sites. Hot Bizzle City Business Classifieds Marketplace offers business automobile electronics fashion household jobs ads realestate list deals shopping s. Gmail is email thats intuitive, efficient, and useful. 15 GB of storage, less spam, and mobile access. We would like to show you a description here but the site wont allow us. Hotwapi. Com is a mobile toplist for mobile web sites. We have over 2000 registered sites. Philosophy Metaphilosophy Metaphysics Epistemology Ethics Politics Aesthetics Thought Mental Cognition.

Great Ideas Of Philosophy 2Nd Edition

var q greatideasofphilosophy2ndeditionPhilosophy from Greek, philosophia, literally love of wisdom is the study of general and fundamental problems concerning matters such as. Philosophy of Sexuality. Among the many topics explored by the philosophy of sexuality are procreation, contraception, celibacy, marriage, adultery, casual sex. BibMe Free Bibliography Citation Maker MLA, APA, Chicago, Harvard. Philosophy of Sexuality Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Among the many topics explored by the philosophy of sexuality are procreation, contraception, celibacy, marriage, adultery, casual sex, flirting, prostitution, homosexuality, masturbation, seduction, rape, sexual harassment, sadomasochism, pornography, bestiality, and pedophilia. What do all these things have in common All are related in various ways to the vast domain of human sexuality. That is, they are related, on the one hand, to the human desires and activities that involve the search for and attainment of sexual pleasure or satisfaction and, on the other hand, to the human desires and activities that involve the creation of new human beings. For it is a natural feature of human beings that certain sorts of behaviors and certain bodily organs are and can be employed either for pleasure or for reproduction, or for both. The philosophy of sexuality explores these topics both conceptually and normatively. Conceptual analysis is carried out in the philosophy of sexuality in order to clarify the fundamental notions of sexual desire and sexual activity. Conceptual analysis is also carried out in attempting to arrive at satisfactory definitions of adultery, prostitution, rape, pornography, and so forth. Conceptual analysis for example what are the distinctive features of a desire that make it sexual desire instead of something else In what ways does seduction differ from nonviolent rape is often difficult and seemingly picky, but proves rewarding in unanticipated and surprising ways. Normative philosophy of sexuality inquires about the value of sexual activity and sexual pleasure and of the various forms they take. Thus the philosophy of sexuality is concerned with the perennial questions of sexual morality and constitutes a large branch of applied ethics. Normative philosophy of sexuality investigates what contribution is made to the good or virtuous life by sexuality, and tries to determine what moral obligations we have to refrain from performing certain sexual acts and what moral permissions we have to engage in others. Some philosophers of sexuality carry out conceptual analysis and the study of sexual ethics separately. They believe that it is one thing to define a sexual phenomenon such as rape or adultery and quite another thing to evaluate it. Other philosophers of sexuality believe that a robust distinction between defining a sexual phenomenon and arriving at moral evaluations of it cannot be made, that analyses of sexual concepts and moral evaluations of sexual acts influence each other. Whether there actually is a tidy distinction between values and morals, on the one hand, and natural, social, or conceptual facts, on the other hand, is one of those fascinating, endlessly debated issues in philosophy, and is not limited to the philosophy of sexuality. Table of Contents Metaphysics of Sexuality Metaphysical Sexual Pessimism Metaphysical Sexual Optimism Moral Evaluations Nonmoral Evaluations The Dangers of Sex Sexual Perversion Sexual Perversion and Morality Aquinass Natural Law Nagels Secular Philosophy Fetishism Female Sexuality and Natural Law Debates in Sexual Ethics Natural Law vs. Liberal Ethics Consent Is Not Sufficient Consent Is Sufficient What Is Voluntary Conceptual Analysis Sexual Activity vs. Having Sex Sexual Activity and Sexual Pleasure Sexual Activity Without Pleasure References and Further Reading. Metaphysics of Sexuality. Our moral evaluations of sexual activity are bound to be affected by what we view the nature of the sexual impulse, or of sexual desire, to be in human beings. In this regard there is a deep divide between those philosophers that we might call the metaphysical sexual optimists and those we might call the metaphysical sexual pessimists. The pessimists in the philosophy of sexuality, such as St. Philosophy is the systematic study of the foundations of human knowledge with an emphasis on the conditions of its validity and finding answers to ultimate questions.

Augustine, Immanuel Kant, and, sometimes, Sigmund Freud, perceive the sexual impulse and acting on it to be something nearly always, if not necessarily, unbefitting the dignity of the human person they see the essence and the results of the drive to be incompatible with more significant and lofty goals and aspirations of human existence they fear that the power and demands of the sexual impulse make it a danger to harmonious civilized life and they find in sexuality a severe threat not only to our proper relations with, and our moral treatment of, other persons, but also equally a threat to our own humanity. On the other side of the divide are the metaphysical sexual optimists Plato, in some of his works, sometimes Sigmund Freud, Bertrand Russell, and many contemporary philosophers who perceive nothing especially obnoxious in the sexual impulse. They view human sexuality as just another and mostly innocuous dimension of our existence as embodied or animal like creatures they judge that sexuality, which in some measure has been given to us by evolution, cannot but be conducive to our well being without detracting from our intellectual propensities and they praise rather than fear the power of an impulse that can lift us to various high forms of happiness. The particular sort of metaphysics of sex one believes will influence ones subsequent judgments about the value and role of sexuality in the good or virtuous life and about what sexual activities are morally wrong and which ones are morally permissible. Lets explore some of these implications. Metaphysical Sexual Pessimism. An extended version of metaphysical pessimism might make the following claims In virtue of the nature of sexual desire, a person who sexually desires another person objectifies that other person, both before and during sexual activity. Sex, says Kant, makes of the loved person an Object of appetite.